Nothing is Still

why tasting notes fail, how experience accumulates, and what wine, music, and memory have in common.

Most people can tell you where they were the first time they heard their favorite song.

And not just the song, but everything around it: the room, the light, the air, the state of their life at that exact moment. The music hits with such force that every other detail of the scene comes into vivid relief, like the background suddenly snapping into focus.

You don’t remember because you were paying attention. You remember because something rearranged you. I can tell you exactly where I was the first time I heard Leon Vynehall’s album, Nothing Is Still, because it rewired my brain for a kind of pleasure I didn’t yet know existed.

It was the morning after one of many lively dinner parties that defined a certain post-Covid moment in 2022, when socializing felt newly possible again and therefore basically mandatory. There was no official cause for celebration, other than that celebration itself was allowed again. About ten people came over and we gathered around the long table in the carport at our old house in New Orleans for dinner. We grilled a couple big steaks and served them with smashed roasted potatoes and smoked pimentón aioli. There was kale salad with anchovy vinaigrette, pecorino and radishes, as was customary.

The next day I woke up in a mild hangover daze and started cleaning the carport. Picking up empty bottles. Someone had brought a bottle of Alice and Olivier de Moor Vau de Vey Chablis. Another friend showed up with a bottle of Domaine Bachelet vieilles vignes Gevrey-Chambertin. A few veladoras remained at the long table under the carport, having been used for sipping mezcal after dinner. I was sweeping the concrete with my earbuds in when the song “Birds on the Tarmac” came on after whatever I had been listening to before.

I stopped what I was doing and made sure to start the album from the beginning, then I kept sweeping. Built from drifting rhythmic cells, blurred melodic fragments, and a low, persistent sense of forward motion, the tracks on this album refuse climax in favor of duration, asking you to stay with them long enough for perception itself to change. I let the album wash over me while dust collected into neat gray lines on the concrete. The music didn’t announce itself as revelatory. It didn’t ask for attention. It simply arrived and stayed, patiently, until I realized—somewhere between one pass of the broom and the next—that my internal sense of pleasure had expanded. There was now a room in my viscera for a kind of aesthetic experience I hadn’t known existed.

I remember all of this with embarrassing clarity: the food, the wine, the weather, the exact moment—not because I tried to remember it, but because the experience carried enough force to reorganize everything around it. That’s how it usually works.

I thought about this moment as I read Meg Maker and Terry Theise’s conversation, “A Defense of Wine Writing”, from the latest issue of World of Fine Wine. It’s a generous, clear-eyed exchange between two veteran wine writers that articulates a shared unease many of us have felt for years: that much of contemporary wine writing—especially tasting-note culture—has become unproductive, aesthetically deadening, and strangely dishonest about what it’s actually doing.

Maker and Theise are skeptical of wine writing that pretends toward objectivity, that treats tasting as a catechism, that flattens lived experience into laundry lists of flavor descriptors and numerical scores. They argue instead for experiential, contextual, literary accounts of wine—writing that is worth keeping, not merely useful to a consumer. They want writing that understands wine not as a static object to be evaluated, but as something encountered in time, through a body, under conditions that matter. And each of their writing styles respectively are great examples of wine writing worth keeping.

I agree with them. And I also think their argument opens onto a slightly deeper question, one that wine culture tends to dodge: where does wine experience actually live, cognitively? How do we hold it? How does it change us? And why do tasting notes—flawed as they are—keep getting written anyway?

I think the tasting note recurs with such persistence because it’s attached to something important: memory, learning, and the desire to hold onto an experience that refuses to hold still.

Credentialed wine programs—Court of Master Sommeliers, WSET, and their cousins—lean heavily on memorization. Varieties, regions, soils, classifications, processes. Tasting grids. Structured recall. There’s a reason for this, and it’s not evil. Memorization is a powerful technology. The memory palace works. Humans are remarkably good at storing information when it’s scaffolded, spatialized, ritualized.

But memorization is often mistaken for experience, or worse, offered as a substitute for it. The grid becomes the thing itself. Correct recall masquerades as understanding. The pleasure of recognition eclipses the messier, more complex, more contingent pleasure of encounter.

Maker and Theise push back against this by allowing wine memory to remain mobile, experiential, even spiritual—less about storing facts and more about recording what happened to you. Their preferred mode of remembering is lived and narrative rather than architectural and fixed. (You may remember how, in an era of deep reconning failure-ridden relationship history, High Fidelity’s protagonist, Rob Gordon, reorganizes his record collection autobiographically.)

Somewhere between these two positions—rote memorization and purely experiential recall—I’d like to propose a loose theory of my own: the matrix.

This concept is borrowed from mathematics, but I don’t mean anything too mathematical. A matrix describes a total field of interrelated data, expressed as a grid. Now, rather than numbers, the data we accumulate over time can take various forms: sensory impressions, emotional states, contextual details, cultural knowledge, social dynamics, personal history. Every wine you drink enters this matrix as a small data set. Flavor, aroma, and texture, yes—but also where you were, who you were with, what you knew at the time, what you were hoping for, what you were avoiding, how open you were to being moved.

The key thing about matrices—mathematically and experientially—is that new data doesn’t simply add information. It changes the relationships among all the existing data.

When your matrix is small, each new experience carries enormous weight. Early wine experiences feel seismic not necessarily because the wines are better, but because there’s less else to compare them to. (I know this because I was that person, briefly convinced I had reached the end of the map because I passed my certification exam.) A single bottle can rearrange the entire field of data. Later, as the matrix grows, experiences tend to register relationally rather than absolutely. You don’t feel less. You feel differently. And your conviction that you ‘know’ anything at all, more or less evaporates.

This is why people often confuse development with loss. The first time something hits you—music, wine, art—it can feel total. Later encounters may feel subtler, quieter, less destabilizing. Not because you’ve become jaded, but because your internal structure has become more complex. Knowledge doesn’t kill pleasure. It redistributes it. Memorization expands the matrix. Experience fills it. Neither is sufficient on its own, and neither needs to cancel the other out. You don’t need to memorize your own life experience—you already know it, simply by having lived it attentively.

I thought about this again watching Kenneth Lonergan’s Margaret. It’s a film that feels almost perversely resistant to summary—not because it’s opaque, but because it insists on being relational. Trauma unfolds sideways. Moral certainty collapses into contradiction. The camera refuses to tell you where to stand, or whom to side with, or when to feel resolved. The most indelible moments are awkward, unresolved, even faintly humorous in their absurdity: Allison Janney bleeding out on the street in a stranger’s arms; Anna Paquin’s painfully misjudged sex scene with Kieran Culkin; J. Smith-Cameron’s portrayal of a mother whose brittle need for her daughter’s affection leads her to lash out in ways that feel inappropriate and totally understandable.

What makes Margaret so demanding is not its subject matter, but its refusal to simplify experience into a single emotional register. Grief does not ennoble. Righteousness does not clarify. Suffering does not arrive with instructions. The film asks the viewer to hold competing truths at once: the protagonist’s pain and her self-absorption, her ethical seriousness and her adolescent sanctimony, the quiet exhaustion of the adults around her, the way a single traumatic event radiates outward into lives that did not consent to carry it.

I probably would not have loved this film when it came out in 2011. Having experienced significant trauma at roughly the same age as Anna Paquin’s character, I don’t think I would have had the distance, or the internal fortitude to see the film clearly. I would have latched onto one perspective and mistaken it for the whole. I would have wanted the movie to take a side.

Watching it now, I didn’t need it to. I could see how meaning emerged not from resolution, but from accumulation: scene layered onto scene, reaction onto reaction, each encounter subtly altering the emotional math of the last. The film hits hard because it hits wide.

What I like most about Maker and Theise’s conversation is that their critique of tasting notes is not theoretical; it’s procedural. They are (obviously) not saying don’t taste carefully. They are saying: change the conditions under which tasting happens.

Again and again, they return to the problem of comparative overload—the professional ritual of tasting forty or fifty wines in a row and pretending this produces meaningful knowledge. Theise is blunt about it: once you pass fifteen or twenty wines, he describes the situation as “false.” The human palate and mind, he contends, simply aren’t built for that kind of abstraction. At that point, you’re no longer encountering wines; you’re watching them perform under contrived conditions.

What they propose instead looks a lot like a practical application of the matrix, even if they never use the word.

Theise talks about tasting the same wine three times over several days, under different circumstances, sometimes even from the same bottle, acknowledging openly that each encounter is partial and contingent. Maker echoes this, saying she wants to live with a wine, to taste it again later, to see how it behaves outside the artificial drama of the comparative tasting lineup. The point is not to triangulate some final truth, but to develop a relationship.

This matters, because you are not the same person across those tastings.

Three or four years apart, your matrix is larger. You have more reference points, more memories, more disappointments, more pleasures, more quiet calibrations you didn’t consciously log. Even three or four hours apart, you’re a different taster: fed or hungry, open or tired, drunk or sober, stimulated or flat. The wine is changing too—opening, softening, tightening, falling apart, pulling itself back together. And even then, as they both note, bottles vary. The same wine, same vintage, same producer can show differently because material reality is not as obedient as our taxonomies would like it to be.

What Maker and Theise are really advocating for, beneath the surface, is a shift away from taxonomy and toward attention over time. Not the accumulation of descriptors, but the accumulation of encounters. Not mastery through classification, but familiarity through repetition. You don’t know a wine because you can name it correctly. You know it because you’ve spent time with it—long enough for both of you to change.

Seen this way, their skepticism toward tasting notes isn’t a rejection of memory or even memorization; it’s a rejection of the fantasy that memory can be flattened into a single, authoritative account. The matrix doesn’t just grow between bottles. It also grows between encounters with the same bottle.

This is where tasting notes start to make more sense to me—not as descriptions of wine, but as timestamps of consciousness. They are not maps. They are artifacts. Evidence that attention happened. Proof that, at a specific moment, something passed through you and left a mark.

They are also factually worthless in the way all memory is factually worthless: subjective, partial, unrepeatable, contaminated by context. The wine changed. You changed. The conditions changed. Accuracy was never on the table. And yet we keep writing them because they’re the only way to prove we were there, in that space of encounter.

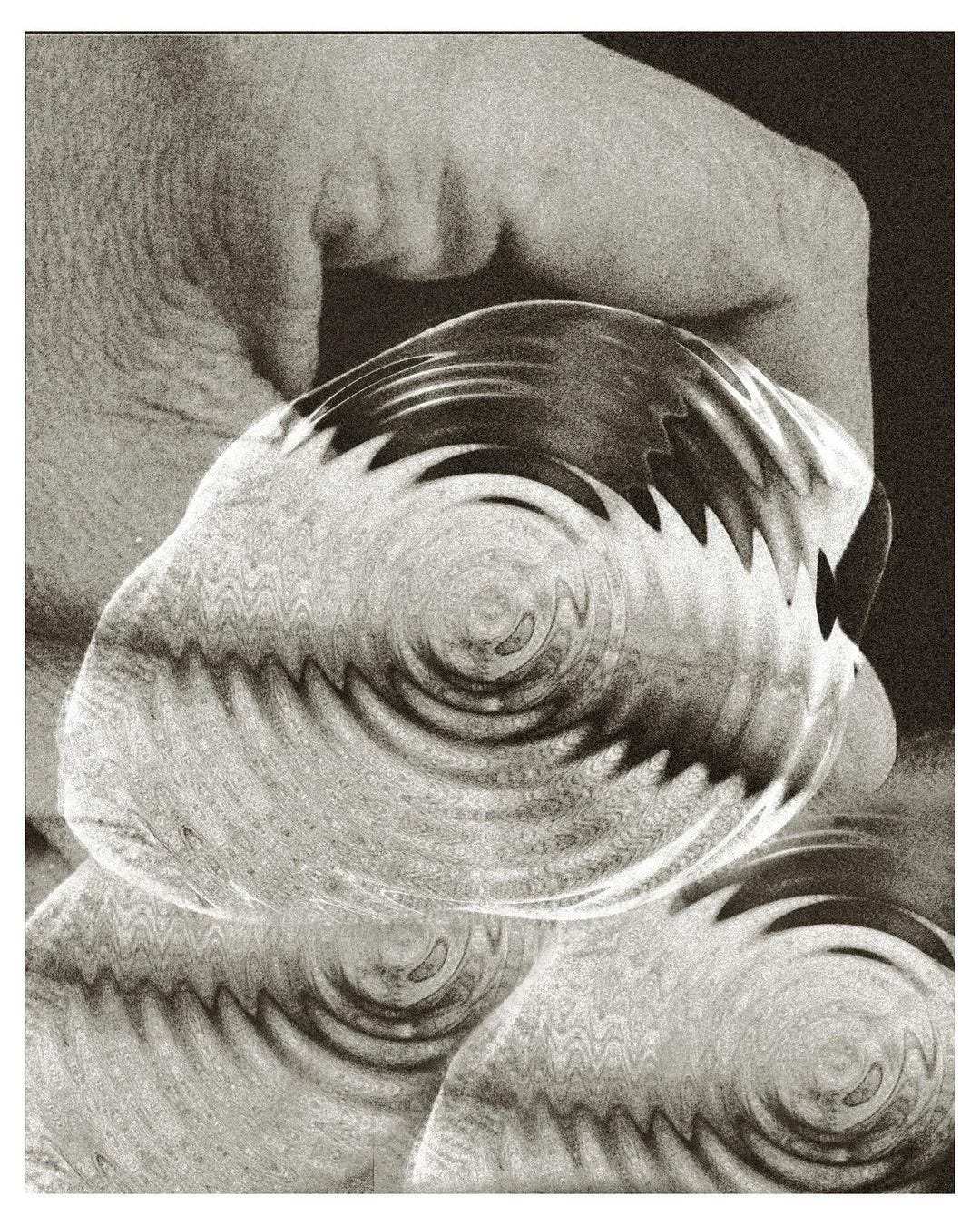

Tasting notes can never tell the truth about wine, but they can tell the truth about having been there. Because they mark a moment when the matrix shifted—sometimes imperceptibly, sometimes all at once. Wine doesn’t hold still long enough to be described, and neither do we.

The only stable unit is the encounter. As Leon Vynehall reminds us: nothing is still.

As a recovering engineer, my brain constantly analyzes data whether I want it to or not. It looks for patterns, and notices discontinuities. Your comments regarding music, and the musical experience that reoriented your thinking rings very true. The same thing can happen with any external stimulus, and those moments, those interactions become guideposts that remain forever visible in memory. Getting back to the data (spurred by your matrix discussion), there’s an uncomplicated state when a process is under control. Things stay within a predictable pattern. Basic, enjoyable wines, food, or music fit a pattern that to a great extent can sadly be little more than background. Then there’s the outlier, the data point that doesn’t fit the set, whether great or horrible. With data we have to understand the outlier and make sure it’s not a change to the pattern of the process. With wine it’s the golden moment to engage at a deeper level and feel everything that is happening at that moment, both with the wine and everything around it. That becomes another guidepost in memory like the first bottle of Selbach-Oster I ever tasted, or the first time I heard Strawberry Fields Forever.

Thank you (and Meg and Terry) for sending my data clogged brain on this path of analysis!

I've read the Maker and Theise article and written to Meg in her post.

Tasting notes at a winery level are perfunctory, at least for me. I do them because I'm requested to do them. I don't even put a blurb on the back of a bottle. Nothing but what is absolutely necessary by law. Those blurbs are boring and useless.

Tasting notes for me these days are SEO/LLM. They are searchable, indexable. The biggest wine companies do them on the most banal wine. I'm considering letting an AI write them in long form for me because they are cookie cutter. Get as many descriptors in as possible to make sure the wine appeals to everyone in some way and so the crawlers grab it for a search. Influencers pick up on those descriptors as well, let them scalp it for their own purposes. Who cares, it means more exposure. I know cynical, but I'm not wrong.

I've never taken a class in tasting or in winemaking for that fact. Not one. I learn by doing, as was said "spending time with it". Using experience, memory (even if nostalgic and imperfect) to remember why I like Sangiovese/Brunello. Or a Merlot that smelled like Jack Daniels when I was too young to drink, but when made properly can show incredible range. Or remembering what Brett or cork taint smells like. All learned by doing, tasting, experiencing.